- Home

- Junko Tabei

Honouring High Places

Honouring High Places Read online

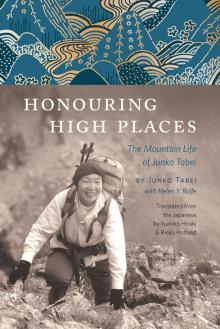

HONOURING HIGH PLACES

THE MOUNTAIN LIFE OF JUNKO TABEI

Junko Tabei and Helen Y. Rolfe

Translated by Yumiko Hiraki and Rieko Holtved

In memory of Junko Tabei, September 22, 1939–October 20, 2016

To Yumiko Hiraki for inviting me to join this endeavour,

and to my family, Brian, Jaiden and Quinn Webster,

for providing the support to delve in.

—HR

For Haraguchi-sensei,

my high-school English teacher in Japan.

—YH

CONTENTS

Author’s Note

Introduction by Setsuko Kitamura

Chapter 1 Avalanche!

Chapter 2 The Meaning of Mountains

Chapter 3 Annapurna III

Chapter 4 Mount Everest

Chapter 5 To the Top of the World

Chapter 6 The Route

Chapter 7 Finalists

Chapter 8 South Col

Chapter 9 The Summit

Chapter 10 Endgame

Chapter 11 Women on Everest

Chapter 12 Mount Tomur, Pobeda Peak

Chapter 13 Aconcagua

Chapter 14 Carstensz Pyramid

Chapter 15 Mountains of Later Life

About Junko by Masanobu Tabei

A Son’s Tribute by Shinya Tabei

Beyond Mountains by Setsuko Kitamura

Life Chronology

Glossary

Acknowledgements

References

Index

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Honouring High Places is the memoir of Junko Tabei, the first woman to climb Mount Everest and complete the Seven Summits. The stories within are based on translated excerpts from several of Tabei’s published Japanese books. Written in first person, each chapter represents experiences in Tabei’s life that she felt were important to share in terms of mountaineering history; they also serve as invitations, encouraging people to go outside and to enjoy nature.

Mine was an enormous job to accurately interpret and express Tabei’s disposition without having met her. I worked closely with Yumiko Hiraki, translator, and dear friend of Tabei, to be certain that every sentence, every word, reflected the era and person in Tabei’s original books. Although challenging, it was a privilege to write about such an accomplished woman and tell her story in detail.

On October 20, 2016, when I was deep in the Annapurna chapter, Tabei succumbed to cancer and passed away. I was awash with emotion. Tabei was part of my daily life by then, and I was saddened that I would never have the chance to shake her hand in person. In addition, we had a book to complete with highlighted sections for Tabei to still comment on. Thankfully, in stepped her loving husband, Masanobu, and her good friend, Setsuko Kitamura, and, of course, Yumiko. Together, and miles apart, we filled in the blanks to unanswered questions. At that time, Yumiko and I, along with Rocky Mountain Books, sped up the process so we could present a finished publication to the Tabei family in fall 2017, marking one year since their beloved Junko had died.

To arrive at the final pages of this book was poignant for me, although I sensed more of a beginning than an end. My hope is that Tabei’s story fulfills its main purpose, which is to offer inspiration and encouragement for people to push themselves in the direction of a challenging goal, whether it be a mountaintop or otherwise. As a certain female mountaineer would have said, “Ganbatte – do your best.”

– Helen Y. Rolfe

INTRODUCTION

by Setsuko Kitamura

Sometime in the early 1990s, Junko Tabei and I saw a pair of elderly ladies at the Nikko train station when we went skiing. Both of them had totally grey hair, and one was tall, the other one tiny. We quietly gazed at them for a while, admiring that they were caring for each other and still cheerfully marching off to somewhere. When they were gone, we giggled and looked at each other, “Haven’t we just witnessed ourselves thirty years from now?”

Though we can never take our peaceful senior life for granted, as nobody knows what is around the corner in the aging years, I would love to become a granny who is as gentle and strong as Tabei has already been, with ice axe in hand (and let us not forget, the occasional application of lipstick, as well).

Elevation 5350 metres, the wave of dusk around the corner and a stabbing cold wind crossing over the glacier. On March 16, 1975, I was standing at Everest Base Camp on the Nepali side of the mountain. I had just arrived there, a few days ahead of the main party, as one of the Base Camp establishment members of the Japanese Women’s Everest Expedition. When all the local porters, yaks and yak handlers left for home, as if being chased away by the impending dark of night, the world of rocks and ice quickly turned desolate. It was my first experience at that high of an altitude, and my job was to manage 15 tons of supplies. I was twenty-five years old at that time, and already I was exhausted. Having almost fallen forward into a temporarily pitched tent, and breathing hard with shaky shoulders, I was caught by the anxious thoughts of what was going to happen in the long stretch of mountaineering that lay ahead.

The very moment I began wallowing in the negative feeling, the tent door suddenly flapped open and a voice full of energy flew into the space. “That’s why kids are kids. Well, well, you stay lying down there and Mom will make tasty croquettes!”

After a short while, on a table in the mess tent, a plateful of perfectly fried crispy croquettes showed up. Dried mashed potato powder, tinned corned beef, half-frozen little onions and crushed biscuits (the stand-ins for crumbled, dried bread) were the modest ingredients used, and somehow, they turned out to be a dish of delicacy. The very taste of those hot croquettes I ate at the skirt of the highest mountain in the world became the symbol of Junko Tabei for me. She was good at managing groups, strong in high altitudes with great mountaineering skills. Always thinking positively, she both had a boyish sense of humour and a sensible nature that kept her grounded. Regardless of celebrity, she stayed an ordinary family woman, cherishing daily life, moment by moment.

The first woman to climb Mount Everest came from an interesting time in Japan, the Meiji era (1868-1912),1 when the Japanese people were introduced to the idea of mountaineering for sport, of enjoying mountaineering in and of itself. Before then, mountaineering in Japan had only been pursued for the purpose of worship. Initially, the hobby, newly imported by Walter Weston and others, prevailed only among men.2 Eventually, in the Taisho era (1912–1926), women of the intellectual class began to join in this European-style play. This is highlighted by Yoneko Murai on Hodaka in the Taisho era, Teru Nakamura on Mount Fuji in the early Showa era (1926–1989), and Hatsuko Kuroda and Kimiko Imai’s climbing on Hodaka, just to list a few.

After the Second World War, the sport of mountaineering expanded beyond a few upper-class women and opened its doors to the broader population. Under the newer “gender equality” philosophy, local mountaineering clubs gradually started to welcome women, and eventually, women-only mountaineering clubs were being born.

In 1949 the long-established Japanese Alpine Club wasted no time in creating the Ladies Section in its Tokyo branch, and in the mid-1950s, Edelweiss Club (1955) and Bush Mountaineering Club (1956) were initiated. The university mountaineering clubs at Waseda and Nihon also began to accept female students, and Tokyo Women’s Medical University established its own mountaineering club.

This era of mountaineering in Japan encouraged and appealed to women who were full of curiosity and the spirit of challenge.

It was also during that time when, in 1956, the Japanese Manaslu Expedition succeeded in the first ascent of that 8156-metre giant. “Not the post-war-era anymore,” and “Japan will revive,” were the general social confidences

that resulted from the success on Manaslu. This same sentiment was also applied at the time to the Japanese ship Sōya that was first used during the war and then was refitted as an Antarctic icebreaker. She became famous for her rescue work in the late 1950s, served for a long time, and is now a museum in Tokyo.

Surfing on top of the booming economy was the enormous youthful energy that spilled out of students and workers who sought to live in the big cities. Also, women were receiving a higher level of education than before, albeit at a more gradual rate. It was no wonder that the interests of men and women alike naturally shifted overseas.

In 1960 Bush Mountaineering Club sent an expedition to India, where members summitted a 6000-metre peak. In 1966 Edelweiss Club travelled to the Peruvian Andes. And in 1965, a women’s mountaineering club called Jungfrau was established in the Kansai region,3 with the concrete aim of “overseas expeditions by women.” They kept their word and reached the summit of Pakistan’s Istor-O-Nal (7403 metres) in 1968. In addition, the Ladies Section of the Japanese Alpine Club had a joint venture with the women’s team of India.

Tabei, who had moved to Tokyo for her university education in 1958, was exactly in the right place at the right time for climbing. Numerous pieces of mountaineering equipment, lighter than before, were invented one after the other, and alpinism was flourishing as a popular sport for ordinary people, including women. There was no doubt that Ryoho, the climbing club she joined after university, was ripe with the spirit behind the slogans “man or woman – it does not matter,” and “next, to the mountains overseas!” In this context, it was natural for Tabei to dream about the Himalayas. At the time, she was seriously into rock climbing in Tanigawa-dake and Hodaka-dake, and so she helped establish the Ladies Climbing Club in Tokyo with the clear purpose of “going to the Himalayas by women alone.”

I first met Tabei in 1973 when I was a rookie reporter for a Japanese newspaper. I was assigned to research the Ladies Climbing Club, which had received a climbing permit for Mount Everest – the first-ever women’s team to go there. Subsequently I shared several expeditions with her, admiring her (ten years my senior) and calling myself her disciple (without her permission). During the time I spent with Tabei, I often saw in her the qualities that make a person a successful, high-mountain climber.

First, she was physically strong, period, particularly in terms of cardiovascular strength. Only once did I witness her suffer from high-altitude sickness, and that was on Shishapangma (8013 metres) in 1981, which she climbed without supplemental oxygen.

Second, Tabei had a high level of practical business skills. The speed at which she typed, in English, the customs documents required for the Everest expedition was impressive; it was as if she were shooting a semi-automatic gun. The image of her typing like that has never left my memory. Then there was her trouble-shooting capability. Her way of finding a solution for complicated problems in prioritized order along with the right judgment call for each issue was breathtaking.

Despite the above descriptions that make Tabei sound like a superwoman, fittingly, she was also unexpectedly a “person of worries.” There was something almost timid in her personality in that she was known to care too much about how others felt. For instance, so far as I know, she cried two times on the Everest expedition alone. First, as we trekked to Base Camp and our team leader surprised us with a sudden departure. Tabei stood forever in the garden of the Tengboche temple where our tents were pitched, looking up at Everest in the distance, her right elbow held high as she wiped her eyes on the back of her hand. The other occasion was after the success on Everest, at a celebration with locals in Namche Bazaar where the Sherpas were based. On the way back to our tent site, slightly removed from the village, after having drunk a bit too much chhaang, she cried hard, like a waterfall.4 She lamented the negative attitude and distorted passion of the teammates who felt they had “missed the limelight of grabbing the summit.” Tabei cried, “Why, we have come here together….”

Tabei was also a sensitive mother who did not forget to draw a picture of a birthday cake with coloured pencils on a postcard and send it, from Everest High Camp, for Noriko, her daughter, turning three years old at the time.

It was probably due to her compassionate personality that Japanese society adopted Junko Tabei as a “star of the mountaineering community” and “role model for Japanese women,” which certainly reflected the era’s shifting values from submissive women to active ones. At the same time, while welcoming “women full of energy,” Japanese society was not ready to accept radical feminists as it was still attached to traditional women figures: good wives, perfect mothers and modest behaviour.

Thus, it was reasonable that Tabei’s brand of conservatism, claiming she was “merely a housewife,” even long after her Everest success, made people feel comfortable. They loved the story of a strong mother, with a young child, courageously conquering the highest mountain in the world.

But a few times I criticized Tabei and her modest proclamations of “Because I am a housewife…,” or “…since it’s me being selfish going mountaineering….” Once I told her straight up: “Hey, there are countless women who wish to pursue their own interests as much as you do. If you continue acting like an elite mom, they would hesitate, like, ‘Oh, I’m not that superwoman like Junko Tabei,’ and the bunch of husbands would take advantage of it, and say, ‘See, she doesn’t sabotage her domestic duties. Can’t you be as perfect as she is?’ In the first place, you don’t want to make a false claim as ‘housewife’ while you make money from mountaineering and presenting speeches, et cetera. You are an authentic professional. You do pay taxes, right?”

My opinion might have had some effect on her, or she herself naturally came to realize her social role as an established commentator in the mountaineering community, because I noticed that in later years when we went on mountain trips together, she started to write “mountaineer” in the “occupation” blanks of hotel check-in forms. Those socially accepted images of her – as a housewife, an established mountaineer or both – were continuously overtaken by her own new activities, much to my pleasure.

Tabei’s new ventures included the start-up of numerous mountain-related social activities and organizations. The establishment of the Himalayan Adventure Trust of Japan in 1990, the International Symposium on Conservation of Mountain Environments (held in cooperation with Sir Edmund Hillary and Reinhold Messner) in Tokyo in 1991, and the Mount Everest Women’s Summit 1995, also in Tokyo, were all initiated by Tabei. These events and their organization gradually revealed Tabei’s ability as “mountaineer and businessperson,” though in a way still faithfully reflecting the ideal woman role model that the new generation had been weaving.

Then, something else – Tabei was not going to sit satisfied in the comfortable chair of the rock star for the mountaineering community or celebrity for the TV screen. In the summer of 1999, she climbed Pobeda Peak (7439 metres) in Kyrgyzstan. Towering on the border of China, this mountain is infamous for its frequent avalanches, a danger Tabei experienced when she was first there in 1986 (on the Chinese side of the mountain, called Mount Tomur). She almost lost her life on Tomur, tumbling down in the throes of an avalanche. Having survived that close call, and then having summitted the peak in 1999, she was honoured to receive the Snow Leopard award for her achievements on all five of the 7000-metre peaks in the Pamir-Tian Shan mountains (in 1985, Ismoil Somoni Peak [7495 metres], formerly named Communism Peak, and Lenin Peak [7134 metres]; and in 1994, Korzhenevskaya Peak [7105 metres] and Khan Tengri [7010 metres]). Tabei received the award a month shy of turning sixty.5

Tabei poured her passion into these lesser-known mountains, out of the public eye compared to the highest in the world or the Seven Summits. Yet, they were still demanding peaks that required more physical power and technical skill than some of the “easier” 8000ers. Her tenacity on these peaks demonstrated her purely personal goal, which had nothing to do with basking in social popularity.

&nbs

p; The same was true in her continuous climbing of several 5000-plus-metre peaks in South America, starting with Tocllaraju (6032 metres) in the Peruvian Andes with youngster Dr. Shiori Hashimoto. Tabei was almost obsessed, again faithfully, with those summits, even though she did not have to prove anything – she was already in the hall of fame.

“Oh, I was pretty nervous, ha, ha!” She laughed as we talked about how an appearance of hers went. While I was writing this article in mid-February 2000, Tabei had just finished a presentation of her thesis – “Study Regarding the Mountaineering Waste at Everest Base Camp” – for a postgraduate course at the University of Kyushu. In 1999 she visited Base Camp, twenty-five years after her summit, and completed detailed research at and around the camp where conditions had been drastically altered by the increased number of climbing teams from all over the world.

By the end of the twentieth century, Himalayan mountaineering had become quite a popular sport. Also, the Japanese yen has been a strong international currency since the 1985 Plaza Accord.6 Familiar with the attitude that “one must keep working no matter what” through the economy’s high-growth period (1960s to 1980s), the Japanese middle-senior age group that had been dreaming about the Himalayas started to apply the same go-getter spirit to peaks in Nepal and China once they reached retirement. Tabei was interested in the mountain pollution that resulted from this trend. Along with her involvement in the Himalayan Adventure Trust of Japan, she became very pro-environment.

After Tabei’s early successes, the forefront of female mountaineers who followed her path and kept pushing their own limits achieved such astonishing goals as climbing the Himalayan high peaks without supplemental oxygen. In 1995 British climber Alison Hargreaves had an amazing success reaching the summit of Everest without oxygen, and solo.7 In 1994 Taeko Nagao and Yuka Endo from Japan displayed their high spirits by climbing a difficult route on the Southwest Face of Cho Oyu.8 In other words, Junko Tabei has become “old school” in the history of mountaineering.

Honouring High Places

Honouring High Places